Archive for the 'Uncategorized' Category

How many for a dollar?

Thursday, July 23rd, 2009 by Bev ClarkThere’s an email newsletter called The Harare Informant that occasionally does the rounds. I like it because its so down to earth and covers bread and butter issues. In the latest issue of The Harare Informant, Mufaro Zhou writes about how much we need change – coins that is! Of course many of us want positive political change as well; what a pity the GNU hasn’t provided it. But when you go shopping you’ll seldom be given change; instead you’re asked to accept a credit note for 12c or you’re forced to buy a bubble gum or something like that. Mufaro had this to say . . .

How many for a dollar?

The advent of the US dollar as the major trading currency in Harare has brought with it many opportunities and terms for people in business. The most common term I can think of is, “dollar for two.” Lately we have seen the rise of “dollar for many.” These terms have also driven some corporates to adopt them in their marketing. Yor Fone is currently advertising using the term “dollar for five.” Guess this means you get to make at most five short calls or simply a single five minute call for one dollar. Either way you look at it, you still have to part with a dollar and use their service for five minutes whether you like it or not. I bet you this is the only city in the world where you have to spend at least a dollar in anything you want to procure no matter how small. One only needs to start doing a research before fully determining the long list of all the products that are being sold in at least double the quantity for a dollar. With no solution in sight of determining the single currency to be officially used in Zimbabwe we the customers will still suffer from parting with at least a dollar (8 Rands) all the time we spend money. It is therefore imperative for the country to seek authorization to officially use the US dollar for the benefit of its citizens. That way we can have access to coins (US cents) making life easier and relatively cheaper for the common man. Why not even go the Mozambique way of officially trading in 3 currencies concurrently. At least life in Bulawayo is better because of their use of the Rand. I don’t know where people get all those Rand coins from leading to commodities being priced from 1 Rand (12 cents) making life improved for residents in Bulawayo. At least with such a pricing system you are not forced to buy something in abundance simply because the smallest denomination in use forces you to. If you are to buy anything abundantly in Bulawayo it will be out of choice, if forced by the smallest denomination then at least it’s only for a Rand.

Dress codes in Zimbabwe

Wednesday, July 22nd, 2009 by Bev Clark

Put on your glad-rags

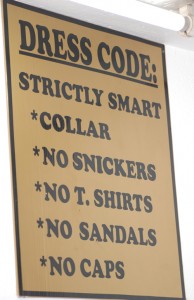

Yesterday evening a friend and I tried a new bar. It was empty besides a single barfly who was talking funerals in Mabvuku whilst nursing a Pilsner. The waiters were so thrilled to see us it seemed like we were their first customers of the day. On the way up the green carpeted stairs I saw this sign.

aa

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

Ride at your own risk

Wednesday, July 22nd, 2009 by Bev ClarkBack in the day when I was much younger I often went to Luna Park when it was over near Glamis Stadium. I loved it. It was always a huge treat. Recently I was delighted to see the return of Luna Park. Its return can’t really be described as triumphant; it’s much diminished compared to it’s former days of full glory. But nevertheless, it’s back and still fun. These days Luna Park is at the corner of 7th and Herbert Chitepo in Harare. It shares the dusty piece of land with weekend soccer games and daily security guard training exercises.

Last Saturday a friend and I pulled in and decided to have a ride on the Shells. I was interested in the ferris wheel but in case of any kind of malfunction I wanted to be close to the ground. The ticket booth has a casual scripted sign on it that says Rides at your own Risk.

And the rides aren’t that cheap either. US$3 for 3 minutes on the Shells, for example. Anyway, we bought our tickets, got on and were flung around, screaming at the top of our lungs, like we were ten again.

Ethics, subjects, and proof

Wednesday, July 22nd, 2009 by Susan PietrzykI recently read a Plus News report entitled: Male circumcision does not protect women. There has been enough literature, media attention, and so on to see that male circumcision has been a hot topic over the years. My interest is not to disagree with the argument that male circumcision can, to a degree, reduce the risk of contracting HIV for that man. In fact, I support the idea of disseminating information and making male circumcision more accessible in Southern Africa. That is as long as the reduce aspect is thoroughly emphasized as male circumcision does not eliminate risk, the potential side effects are conveyed, and it is not an imposed procedure.

The questions I do wish to raise concern the lengths that are being taken to scientifically prove the relationships between black African male circumcision and HIV risk for black African men and women. And relatedly, the potential for unintended consequences when the path followed is such a rigorous and relentless insistence on absolute, detailed quantitative scientific proof. My overall concern is this. The Plus News headline I mentioned could just as easily read: Clinical trial comes to an end, 25 women contracted HIV. When I think about that alternative headline, my mind goes a couple directions. For all the big money that was spent on the trial, perhaps the money would have been better spent trying to ensure the 25 women (and others) did not contract HIV. And further, if the majority of men in the US were uncircumcised would the funders of scientific trials have the same comfort-level to round up some HIV-positive men, along with their HIV-negative female partners, and engage them in a trial knowing that some percentage of those HIV-negative American females will end up HIV-positive. I suspect not.

There are several things I’m getting at here, which relate to my uneasy feelings about trials concerning male circumcision in general and also the particular trial in Rakai District (Southern Uganda) highlighted in Plus News. Firstly, as part of the effort to scientifically prove that male circumcision reduces HIV risk, a trial immediately offers some men access to the procedure while others must wait until the study is completed. Secondly, in order to get the scientific proof, along the way, some of the subjects have to become HIV-positive. Thirdly, the scientific proof for the Rakai District trial is, to a degree, based on 159 Ugandan women honestly reporting that they had sex only with their partner over the trial period. Those three points raise a complicated set of ethical and methodological questions. Before I go any further, let me outline some of the parameters concerning the Rakai District trial as highlighted in the Plus News article (which draws on two articles in the 17 July 2009 issue of Lancet).

The two-year trial included 922 HIV-positive male subjects. At the start, 474 were circumcised, and the other 448 were not. Additionally, the trial included 159 HIV-negative female subjects, the partners of a subset of the 922 male subjects. There were 92 couples representing an HIV-positive circumcised male with an HIV-negative female partner. And 67 couples representing an HIV-positive uncircumcised male with an HIV-negative female partner. The couples were basically told to go about their lives, and involvement in the trial importantly provided a range of STI/HIV-awareness services participants might not have otherwise accessed (albeit likely intensely biomedical oriented awareness services). Follow ups were made at six-month intervals to ascertain if any of the 159 female subjects had acquired HIV from their male partners. Of the 92 couples involving a circumcised male, 18% (or 17 women) tested HIV-positive. Of the 67 couples involving an uncircumcised male 12%

(or 8 women) tested HIV-positive. Thus the conclusion, male circumcision does not reduce HIV risk for women. I know this is not exactly the case, but still. In a certain way one result of obtaining that scientifically proven conclusion is that 25 Ugandan women became infected. The researchers do not state as much directly, but do hint at this possibility. A number of the circumcised male subjects did not follow the advice to abstain from sex for six weeks following being circumcised (to let the wound properly heal). When that advice was not followed this was the window in which a greater number of women contracted HIV from their male partners. Thus an argument can be made that had the men not been circumcised their female partners would not have become HIV-positive.

I know many won’t like what I am writing. The trial itself did not infect 25 women. The trial itself was administered by a team of experts and was approved by numerous Ugandan and American ethical review boards. Additionally, many would tell me the advancement of scientific knowledge has always involved unintended consequences. And those consequences have to be put in the perspective of the greater good. But when it comes to clinical trials around male circumcision among black Africans, there are some particular and unique dynamics that don’t sit well with me. Particularly, when these types of trials are put in the bigger picture, I can’t help but wonder about the notion of engaging black Africans to be subjects for the advancement of scientific research when it is predominantly the Western world wanting to pursue said research. And ask. Are there multiple

(conflicting) ideologies at work in making the foreskin of a black African penis a form of difference that warrants scientific study?

To return to my earlier wording, the lengths that are being taken to scientifically prove. Awhile back, within a listserv discussion, I commented that I am frustrated by the trends PEPFAR, the Global Fund, Bill and Melinda Gates, etc. have ushered in, they are not entirely new, but it seems they are with such greater force than ever before. This incessant demand to prove things, particularly quantitatively. To my mind, and I’ll be blunt. Enough with the proof around male circumcision. It’s not a quantitative contest. I would argue that enough clinical trials around male circumcision have been conducted. It is now time to continue on with integrating the results into long-standing HIV/AIDS information dissemination and service provision efforts. Specifically along three lines: 1) Male circumcision reduces, but does not eliminate, HIV risk for men; 2) Male circumcision, like nearly all medical procedures, contains risks and requires post-operative care; and 3) Male circumcision is a possible option for informed/consenting adults.

Violence and masculine performances

Monday, July 20th, 2009 by Susan PietrzykAccording to Zimbabwe’s 2005 Demographic Health Survey (DHS), 47% of women aged 15 to 49 reported an experience with either physical or sexual violence in their lifetime.

Statistically speaking, it is difficult to make an over-time comparison because the 1999 DHS did not collect data on incidences of violence against women. I suspect, and literature supports the argument that including incidences of violence in the 2005 DHS is the result of recognition that violence against women in Zimbabwe has been increasing. Beyond statistics I see the pressing and complex question as follows. If you ask a Zimbabwean man: What do you think your wife would do if you hit her? Or a Zimbabwean woman: What would you do if your husband hit you? I suspect, more often than not, the answer to either of those questions would not be an immediate, without hesitating…. I would never hit my wife. Or my husband would never hit me. Instead, a male or female respondent would pause. And think. Their pausing and thinking is because that act of violence in the home is a very real possibility. That real possibility is troublesome, but to me equally as troublesome is resting in a space where it’s ok to pause before answering the questions I posed. In Zimbabwe, copious are cultural practices, traditions, perspectives around normative spousal roles, forms of peer pressure, extended family dynamics, failures to communicate, economic hardships, and so on which explain away why domestic violence exists. Yet, these types of explanations only scratch the surface in trying to understand the baseline crux of the matter: What prompts one human being to inflict physical and emotional harm on another human being?

With an interest in exploring the issue of violence, International Video Fair Trust (IVF) brought a group of seven men and seven women together for a week of discussions during the first week of July. These in-depth discussions were filmed and I served as director for the week’s programme and the film project. The methodology follows that used for the 2008 filming of IVF’s Sex in the City of Harare. The basic idea is this: Create a safe space for people to speak and debate openly and honestly. Encourage the participants to move beyond the predictable conversation. Capture the discussions, the emotion, and trepidation on film. Make a documentary film which presents the story that unfolded during the week. Screen it locally as a way to guide individual communities to engage themselves in similar conversations. In the end, both the week long discussions which are filmed and in turn, the documentary film itself, serve as an awareness-building, educational, and advocacy tool. In this case, advocacy which ultimately is about helping people understand that there are options other than violence when it comes to resolving disagreements.

One reason this participatory discussion methodology works well is that nearly all pressing issues have, at their core, simple solutions. Just that getting to that simple solution is a layered process which requires honest, probing, and direct conversations about what is preventing positive change from taking place. Therefore, with respect to the topic of violence is the line of thought that it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to realize that the simple equation violence = harm is not sufficient to bring about an immediate shift to non-violence. Instead, making the shift involves letting an introspective process play out. This is to say that it is easy to assert that violence is wrong, but much harder to actually make the necessary changes at both personal and societal levels to enable violence-free lives. The latter step to actually change requires an intellectual thought process to recast ways of thinking and ways of being. Further it is not merely a matter of women demanding men change. Or men demanding women change. Change has to come from within. And it doesn’t happen overnight. What the week of filming brought forth was a group of people who I observed as intricately conflicted individuals, very much at different points with respect the introspective process that tries to understand and reduce violence. The discussions provided space to recognize the complexities at work and to reflect on why you yourself and people in general are resistant to change.

Now that the filming is complete, I’ve been trying to conceptualize a story for a film. And have been thinking a lot about performances of masculinity and their potential relationship to acts of violence. In this instance, by performance of masculinity I mean the ways people (men and women) put on an act as a way to assert authority and control over another person. The thing about these kinds of performances is that to an outside observer they often make evident contradictions. But to the person engaged in that performance of masculinity likely the contradiction is not seen. The inability to see the contradiction is because what’s at work is a performance to get what you want, what you think you are entitled to. And what you want, your entitlements, and the ways in which you obtain them do not necessarily bring forth contradictions in your mind. For example, it’s not unheard of for a man to speak gushingly about loving his wife. When that husband enters discussion concerning, for example, labola, conjugal rights, and/or household duties, there are ways that conversation becomes about the authority and control the husband feels he has over his wife. Engaging in a discussion of wanting that power is a performance of masculinity, while pursuing that desire might result in the husband using physical and/or emotional violence to get his way. The outside observer is likely going to look at that situation and ask: If you love your wife why would you hit her? And go on to say: That’s a contradiction. But not to the husband, as he feels he is rightfully doing what is necessary to get what he wants.

Another example might be a woman who intelligently and passionately asserts that it is wrong for a man to be violent toward a woman. This assertion might become so strong in the woman’s mind that she will make maneuvers and strategize how to ensure her husband does not become violent. Whether it involves being a perfectly obedient and subservient wife or gaining economic independence within the marriage and keeping those earnings for herself, there are ways she is engaged in a performance of masculinity, working to position herself as the person with authority and control of the relationship. The outside observer is likely going to look at that situation and ask: If you love your husband why do you manipulate him and withhold from him? And go on to say: That’s a contradiction. But not to the wife, as she feels she is rightfully doing what is necessary to get what she wants.

The paragraph above is a tricky one. Probably not the status quo line of analysis around the topic of violence. After hearing fourteen Zimbabweans talk about violence for five and half days, it has become crystal clear to me that the status quo analysis is not enough. All status quo gets to is the far too easy space of relying on broad sweeping statements such as men are socialized to be violent, women must be empowered, culture accepts violence. But those concepts—socialization, empowered, culture—often are either loaded or vacuous, they don’t go very far in actually telling us much about the nitty gritty detail of the dilemma. What’s much harder, yet in my view far more important, is to open up. Be honest. And dare I say, get in touch with your feelings. Recognize your own masculine performances that concern desire for power and in turn the ways ensuing actions towards others might be contradictory. Fourteen Zimbabweans admirably spent a week travelling down this path of honesty. The door is open for the next fourteen.

Alternatively, if broad sweeping statements must be invoked, my suggestion would be the one that is the broadest of the lot. This being. Much of Zimbabwe’s history (and world history for that matter) has involved one big chess match of masculine performers and their quests for power. To be successful in the quest might require violence, so the wisdom contradictorily goes. Flows then that individual homes and extended families in the present often end up smaller-scale versions of this chess match.